An Insider’s Guide to Dnipro

Opening up a Closed City

In August 2020, we interviewed Roman Skrypnyk, our insider guide, who shared with us about growing up in Dnipro, one of the Soviet Union’s “closed cities”. Today Dnipro and all of Ukraine is under siege as a result of Russia’s unjustified invasion.

Poplavok Cafe ©

Returning to that interview, let’s begin by explaining what we know about the Closed City concept. Stalin started it in the 1940s making a number of cities where top-secret research and projects were being undertaken, ‘closed’ meaning you would need permission to live or leave there or enter without authorisation, the basic rights we should all expect of freedom of thought and freedom of movement were denied. If you had the misfortune of your car breaking down in the zone encircling the city – you couldn’t enter or expect any help, you’d be met with suspicion.

Roman, is a videographer who is ‘a little obsessed with architectural and street photography. There’s a lot of brutalist architecture to explore here in Dnipro and in the former USSR. I’m fascinated by the lines and light’.

Palace of Pioneers ©

Greyscape Q&A

Why was Dnipro a Closed City? Was this in your living memory? How did it impact on you and your family?

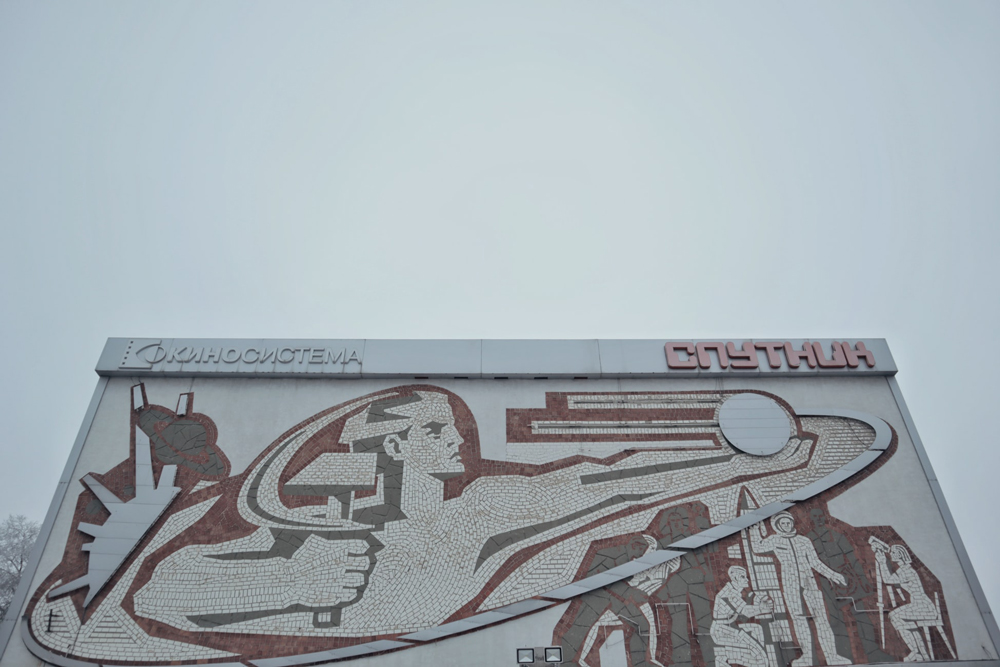

Dnipro was home to Konstuctorskoe Buro Yuzhnoe and Yuzhmash – where sputniks (satellites) and rockets engines were built. The famous USSR missile “Satan” was built here, the two factories are still operating, I’ve actually got a friend who works at Buro Yuzhnoe. The city was and is a centre of rocketry and rocket science. We have full-size models of those rockets on the streets. Some buildings resemble that epoch, for example, the Palace of Pioneers.

Sputnik Cinema

I was born in 1994, three years after the end of the Soviet Union. Living in a Closed City impacted every citizen, and much more so here than in the west of Ukraine. Distrust of strangers hung in the air. From the perspective of being a photographer, and particularly when thinking about street photography there was a real sense of wariness.

Why wary?

I suppose it was a combination, a natural caution that had seeped into people’s behaviour as a result of the Soviet era and the proximity of our Eastern neighbour (before Ukrainian independence). There’s an idea that goes back to the Russian empire of the watchman’s syndrome.

Greyscape note: In the UK we call this ‘job’s-worth’, minor officials who don’t see their function as being to help the public but rather to exercise all their powers to obstruct (hence ‘it’s more than my job’s worth’ to help you) is known as the Watchman’s syndrome, the Watchman may not have any real power but it is enough to obstruct and delay and just say no.

Roman goes on that particularly in a Closed City, the Watchman’s syndrome will operate to not let anyone in, not let anyone photograph anything.

Are locals not particularly open to strangers?

In a Closed City, those who are not integrated into the system are strangers. Now the system is gone, but the sensations and inertia seem to remain. Especially when you find yourself in a crowd of young engineers (there are many in Dnipro) – sometimes you can feel the breath of the USSR, in behaviour, perhaps in a worldview, and of course in the attitude towards humanities.

In the last few years more generally that behaviour has mostly disappeared. I studied in Lviv in Ukraine and only when I had the chance to compare did I really notice the difference. Lviv is a city where you can just take street photos generally without problems, use a restaurant where there are other diners present to shoot an interview. Basically, nobody cared. When I returned home to Dnipro I’d forgotten that the city is very different in character and just carried on snapping. People stared at me and made it clear that this was not usual behaviour. By the way, journalism here in Dnipro has remained at about the same level of difficulty as it was in Soviet times – there is a high entry threshold, outsiders will not be allowed. Well, almost everyone is somehow connected with the authorities.

Palace of Children and Youths ©

Poplavok Cafe ©

Are there places that photographers can now feature? or are certain areas still prohibited?

Everything is still closed. Once I tried to get into the factory area – to make multimedia material about the plant and the bureau. It had been negotiated through Kyiv’s Space Bureau however when I arrived I was still refused entry to Yuzhmash at the local level.

Greyscape note: Yuzhmash is a rocket manufacturer

Meteor Building ©

Has the bureaucracy affected your photography and the subjects you choose?

Not so much on my photography as much as on the behaviour of the people living in Dnipro. If you are seen wandering around with a camera or operating a drone, you felt like a stranger until now – it is 29 years since USSR ended. Definitely there is a post-Soviet effect -it has impacted even more in other former Closed Cities. It has also affected the composition of the population. There is a disproportionate number of engineers, mathematicians and physicists in Dnipro.

Do you mean they are an intellectual elite?

Let’s say they are ahead of the pack. Art is designated in people’s minds as something to be enjoyed as a hobby.

Is there an art and photography scene?

Yes, there are several galleries and exhibition spaces

Poplavok Cafe ©

Why is the city also called Dnipropetrovsk?

Dnipro was renamed in 2016 as part of Ukraine’s de-communization process following a new law in 2015. For residents, nothing has changed much, because no one bothered with the full name anyway, they always shortened the second part and said ‘Dnipro’. To break it down Dnipro for the river it stands on and Petrovsky for a Soviet politician, Grigory Petrovsky.

Roman’s top five buildings in Dnipro to photograph:

Hotel Parus ©

Botanical Garden of Oles Honchar Dnipro National University ©

Hotel Parus – the highest building in the city, however, it was abandoned with the dissolution of the Soviet Union. It is seen as a symbol of corruption as all the building rules were ignored for it to be built. The 22-metre trident was painted later, in 2014, by Dnipro FC’s ultras as a symbol of the city being Ukranian – against the background of the conflict in the east of Ukraine.

Poplavok cafe – inspired by space exploration as it looks like a UFO. It’s located near Hotel Parus

Pioneers’ Palace – there is a cool modern theatre functioning here. The building itself was without doubt inspired by the idea of an orbital space station with its footbridges spread out.

Meteor, the Ice Palace of Sports – it used to be the electronics market – I went there with my father when I was a child.

Monument to the War 1941-45 (Monument of Eternal Glory) is located on the edge of the hill – so it really looks high.

Monument of Eternal Glory ©

Any insider tips for visitors?

– Damodara – local vegan restaurant

– Кеды искусствоведа – nice choice of beer and snacks

Hotel Parus Dnipro Image Roman Skrypnyk

Try Chebureki (the national dish of Tartar Crimea)

Cheburechnaya №1 – nice thin baked chebureks

Palace of Pioneers ©

Favourite films?

Hotel Grand Budapest by Wes Anderson

What we do in the shadows by Taika Waititi

All photos and videos Copyright of Roman Skrypnyk

Find Roman on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/timesnewroman14_shots

Roman’s videos:

Dnipro Arch