Negozio Olivetti by Carlo Scarpa

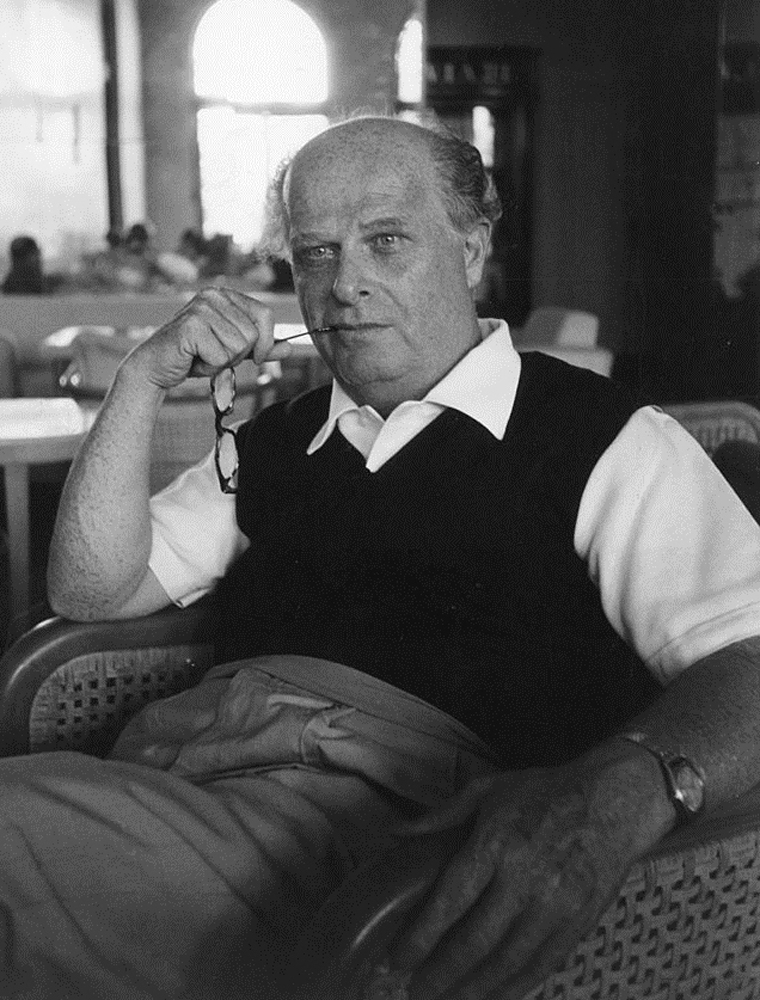

Adriano Olivetti a man with a vision who worked to ensure that it was hardwired into his company.

Carlo Scarpa for Olivetti 1957 Images FAI Negozio Olivetti ©

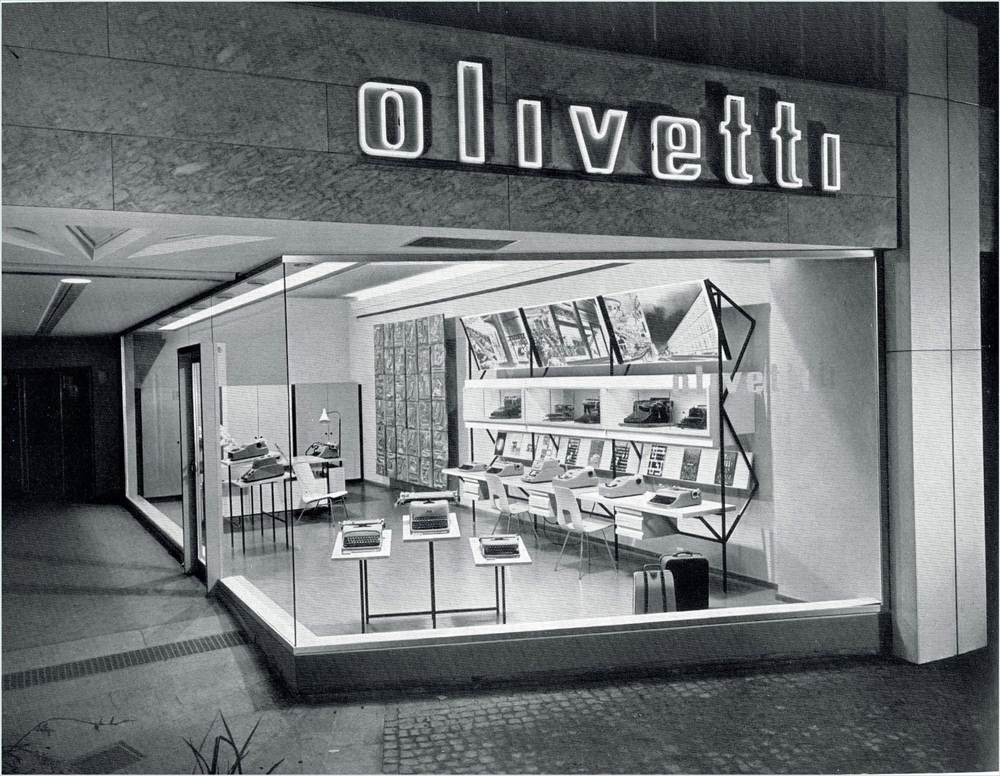

By the 1950s Olivetti was the last word in cool industrial design. Its stylish typewriters were a key global component of commerce and industry, education and creativity. What brought the company to this pinnacle of design and commercial success were two people, Camillo Olivetti and his anti-fascist activist son, Adriano.

There are a lot of people who talk a great deal about improving the lot of others and that’s all they do, pontificate. Fired by his political activism, his loathing of fascism, Adriano Olivetti materially improved the experience of his workforce and with that heralded a new way to define the employer-employee relationship.

The family’s extraordinary influence on the history of product design and technical innovation began when Camillio Olivetti, created Italy’s first ‘dedicated typewriter factory’ in 1908. An electrical engineer by training, he was born in 1868 into a comfortably off family in Ivrea, a small town 50 miles outside Turin. Early on he spent time in the US as the country was fine-tuning modern manufacturing techniques that were changing the world. When he returned to Italy he started importing typewriters but of course, as we all know, he figured out very quickly that he needed to make his own. The first Olivetti typewriter produced in Camillo’s factory was the M20. As the business thrived Camillio developed his factory and his choice of designers unsurprisingly were important trailblazers. Olivetti’s history is informed by the hiring of visionary designers who collaborated with the tech guys. In bringing Gino Pollini and Luigi Figini from Gruppo 7 to design the company’s new factory, Camillo put in place a trend that would continue for more than half a century.

Image Seier+Seier

Image FAI Negozio Olivetti

Xanti Schawinsky for Olivetti Studio 42 CC BY SA 3.0

In October 1922 Italy lurched to the far-right. The March on Rome brought the fascists into mainstream politics and put Camillo’s son Adriano’s in their crosshairs, care of his anti-fascist views, activism and heritage. By 1938 racial laws, adopted from Germany targeting Jews sent the family and Camillo into protective mode. Regardless that Camillo was not a religious person and that his wife was Waldensian, the family and the company were at risk, the decision was made to hand the company over from father to son whose Jewishness was diluted by his mother.

The war years were tough, at one point Adriano was imprisoned in Regina Coeli Prison in Rome until he managed to escape. By 1943 most of the immediate family had escaped to Switzerland. For the elderly Camillo life became more precarious. He was moved to a village close to the Swiss border where he died two months later.

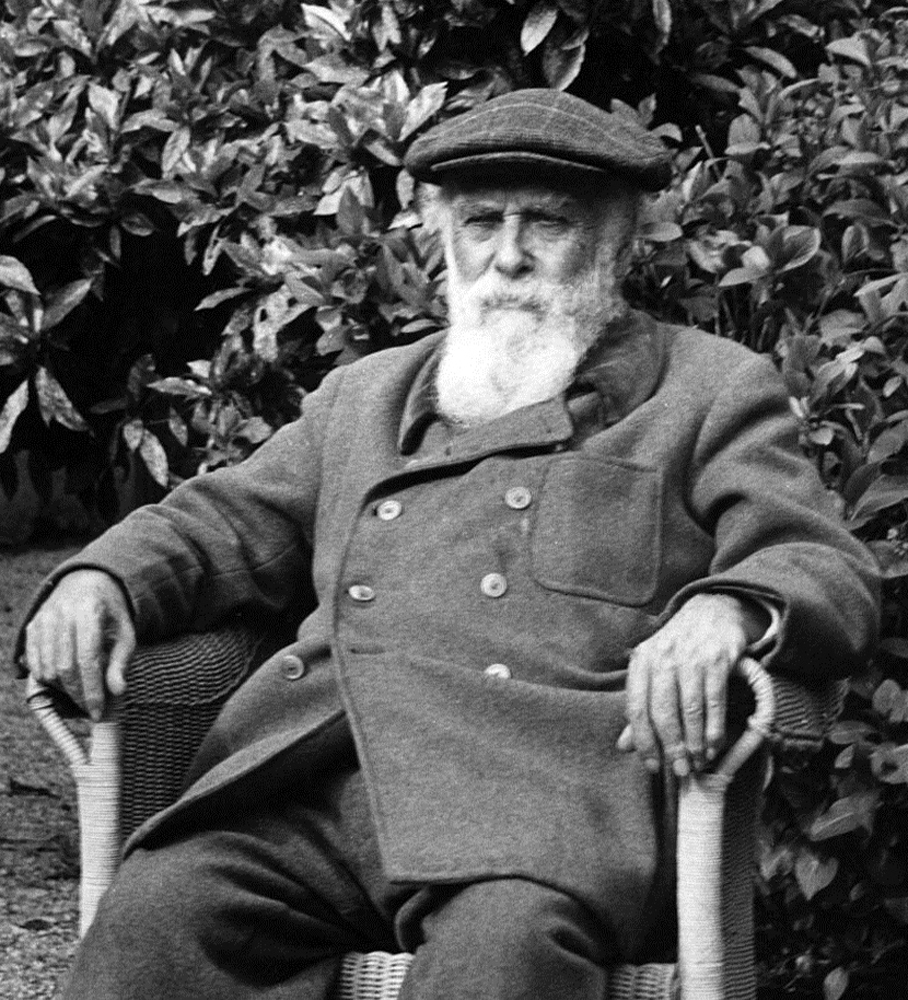

Memorial to Camilo Olivetti, Ivrea Image Laurom CC BY SA 3.0 / Camillo Olivetti (top) and Adriano Olivetti – Mondadori Publishers- Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

As soon as the war ended Adriano was preparing his company for … well you could say, growth. The most creative minds in the arts, architecture and technology were employed and deployed.

By 1952 Olivetti had plants in Turin, Apuania, Barcelona and Glasgow. Rather like Apple’s genius in transforming the MP5 music player from a clunky piece of electronic kit into the iPod, Olivetti brought sophistication and appealing design to their typewriters. Adriano had taken a small company and had grown it into a 40,000 employee business with a presence in 17 countries.

Olivetti Negozio 1966 CC BY SA 4.0 Andreafist

All the while Olivetti remained faithful to Adriano’s fundamental beliefs about how a company should operate, how its employees should be treated and how the living conditions of the workers were an integral part of the company’s commitment. Offering staff access to a sponsored nursery, creating dedicated imaginative housing for workers and their families were just some of the benefits introduced. All these elements gained substance in the La Serra Complex in Ivrea.

La Serra Complex Ivrea Olivetti Image @NickBallon

La Serra Complex Ivrea Olivetti Image @NickBallon

Ivrea, still the company HQ, was developed to reflect Adriano’s vision.

MoMA in New York featured the company in its 1952 exhibition, ‘Olivetti: design in industry’. The catalogue described the company as

‘the leading corporation in the western world in the field of design. For patronage in architecture, product design and advertising, it would indeed be difficult to name a second.’

The company took the design world by storm and as the years rolled on it was innovation after innovation, designs that became instant classics.

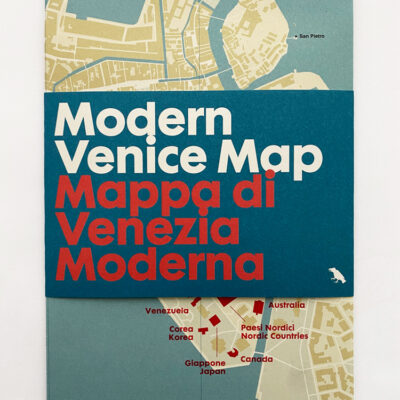

An apt description of the coming together of the brilliant and highly thought of Carlo Scarpa in 1957 and Adriano is a marriage of minds. Adriano commissioned Venetian-born Scarpa to transform a small space at number 101 Piazza San Marco in Venice. For Adriano, the project was more than a shop it was a destination and a showcase for his company’s designs. The location mattered, under the colonnades of the Piazza San Marco – an incredibly memorable address as Venetian society and arguably as Italy was becoming a more and more fashionable destination. You could say placing the store in one of the world’s most famous addresses. Olivetti was clear he wasn’t looking for just another store – he spoke of it as a company ‘business card.’

Image Jean Pierre Dahlbera CC BY SA 2.0

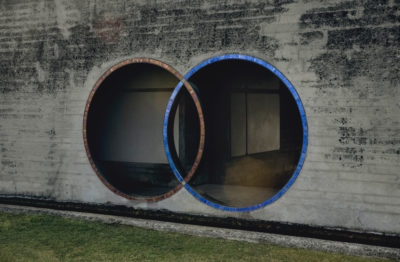

Scarpa’s first impressions were of a narrow space, poorly lit with access to the second floor at the back. Unfazed he said, ‘for a king one can create a royal palace’ By the time he had finished the project to create Negozio Olivetti it had ‘two long galleries, a central staircase and a bold sculpture by Alberto Viani, Nude in the Sun’. And, not just any staircase – described by FAI

‘The staircase is an authentic masterpiece….the exposed screws accent the central axis of the room, while the irregular stairs seem suspended and break up the showrooms space’.

Aurisina marble from Trieste was used, the typewriters sat on rosewood shelves with stainless steel supports ‘African teak balconies, metals and stone are all found alongside traditional Venetian stucco and mosaics revisited in a modern key’ Marmorino was used on panels – an ancient Venisian by-product of the marble industry.

In a way, if one freezeframes a moment it really does give a sense of the scope and vision of Olivetti. Whilst Scarpa is building something timeless in Venice, four hours drive away in Ivrea the Electronic Research Lab is creating the next generation of products. Headed by Mario Tchou this experimental space is taking Olivetti deeper into the world of electronics. It was here in the late 1950s that the Elea 9003 was created incorporating an Ettore Sottsass design, this was Italy’s (and for many, the world’s first) mainframe computer. For a time the company even leapfrogged IBM. By now Roberto, Adriano’s son was working in the company.

Maybe it was Adriano’s unexpected death on a train in 1960 followed a year later by the death of Tchou that marked the beginning of the change in the company’s fortunes and broke its habit of being first past the post. It led to General Motors buying part of the business in 1964, in a chain reaction that had far-reaching consequences. Olivetti didn’t dip its toe into the electronics market for quite a few years after that. Olivetti’s 1959 acquisition of Underwood Typewriter Company in the USA didn’t work out well and while the 1970s delivered yet another set of design icons – in reality by the 1980s the company was having some real problems and led to a merger.

As for the Negozio Olivetti it was always bound to get caught up in the company’s problems and was deemed to have outlived its usefulness by the late 1990s and the decision was made to close the showroom. It remained a shop but not the kind one would have imagined – those Scarpa designed shelves were filled with tourist-tat. Thankfully FAI came to the rescue in 2011. Today the shop, now a museum, has been returned to Adriano and Carlo’s vision, visitors can see vintage Olivetti typewriters, printing calculators and iconic marketing materials.

Whilst the post-millennium Olivetti doesn’t have an Adriano or Camilla, it is on a solid footing.

The Italian philosopher Umberto Galimberti spoke on Swiss TV in 2010 about Adriano’s breathtaking era and really gets to the heart of the man ;

‘Olivetti would not survive today, indeed it has not survived. The reason for this is that if you focus on mankind, then invariably you are kept in check by those who focus on money. Olivetti had a dream, a very important utopia, and created a culture that had man and his realisation as the centre of output.

Olivetti invited industry to look at society. I would have liked to point this fact out to Adriano Olivetti, and not because I find fault with his intentions, but simply because I see how society works today. It works exactly like a technostructure, with men inserted in the company to be parts of the machinery, not individuals with their own desires, aspirations and will. This is where Adriano Olivetti’s utopia lies’.

Olivetti in exhibitions:

Olivetti: Beyond Form and Function 2016 at the ICA London

Olivetti: Design in Industry 1952 MoMA, New York

Just some of the product designers, artists and architectures commissioned by Olivetti and the products

M40 typewriter 1929 Camillo Olivetti with Gino Levi Martinoli

MP1 Case designed by Aldo Magnelli with mechanical design by Riccardo Levi

Picasso paint a mural for the salesrooms

Olivetti Underwood Factory Philidephia architect Louis Kahn,

Olivetti Electronic Cente, designer Corbusier

Lexicon 80, Office typewriter Architect-designer Marcello Nizzoli

The sending receiving teleprinter 1948 Architect-designer Marcello Nizzoli

Studio 42 typewriter Xanti Schawinsky

Lettera portable typewriter 1949 Marcello Nizzoli

Giovanni Pintori as Art Director 1952

Elea 9003 1956 Ettore Sottsass electronic devices and mainframe computer.

The ‘visual jukebox of the imagination’ 1970 for MoMA’s Concept and Form exhibition Ettore Sottsass

Lettera 33 and Lettera 48 Ettore Sottsass

Valentine typewriter 1969 Sottsass and Perry King

Sculpture for Olivetti Store 5th Avenue NYC 1954 Constantino Nivolli

Images Copyright of Christopher Iwata unless otherwise noted

With thanks to FAI Negozio Olivetti and Nick Ballón

Olivetti Valentine 1969 CC BY SA 3.0